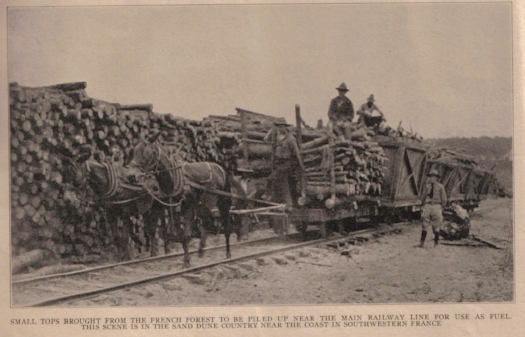

In 1917 during the Great War, the war effort needed lumberjacks. They needed lumber for building barracks, hospitals, trenches, and tracks. Shipping was impractical; the lumber needed to be obtained near the front. They needed land cleared for airfields and railways. They needed experts, and they recruited from among the best and brightest of America’s storied and rugged logging industry.

Charlie was born for this

Charles Emil Swanson was born December 5th, 1890, in the great Northwoods of Wisconsin near the township of Harrison–between Tomahawk and Enterprise and north of Wausau about 40 miles. It was the height of Wisconsin’s lumber boom and logging was the biggest industry in Wisconsin. Charlie’s father, Gustaf Emil “Ed” Swanson had recently immigrated from Sweden with Charlie’s mother, Matilda. Ed was a Lumberman. His parents, Samuel and Johanna, and Ed’s brothers, Ernest and Charles, were also nearby, working in lumber, and also recent immigrants.

Charlie spent the first 10 years of his life near lumber camps and sawmill towns. There were many grand things to see in the booming frontier: trees so old and so large that three men together couldn’t reach around them and the sky was dark even on a bright sunny day in June; logs floating down the river in the spring in such quantities that one wasn’t quite sure there was a river underneath; railroads being built as fast as Paul Bunyan could swing an ax opened up vast new areas for development.*

When Charlie was 10, his family bought farmland near the Wisconsin River about 5 miles south of Wausau. In some ways, this wasn’t a big difference for the family because Wausau was still the same world–still in the middle of lumber country and booming enterprise. On the other hand, the family had a permanent home and Charlie had chores caring for the family’s Guernsey cows.

Education was important and Charlie rowed across the Wisconsin River each day to attend school in Weston. After finishing district school, he attended and graduated from the Wausau Business College. He was employed by the B. Heinemann Lumber company in Wausau before moving west to the growing lumber areas in Montana. There he settled in Wagner, a town on the Great Northern Railway, where he was manager of the lumber yard for the Rogers-Templeton Lumber Company.

The United States goes to War

The US entered the war in April 1917, and by May, were organizing lumberjack units that would eventually become the 20th Engineers, an Army regiment still serving today as part of the 36th Engineer Brigade based at Fort Hood, Texas.

Upon his first visit to France, US General Pershing initially requested a force large enough to cut at least 25,000,000 board feet per month. By the end of the war, the 20th Engineers were producing 2,000,000 board feet of lumber daily. One report said that the 20th Engineers operated 282 sawmills and one said 81 sawmills, but however many sawmills, the production was incredible.

In a report called “The American Lumberjack in France,” published in American Forestry in June 1919, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Greeley wrote after writing about numerous feats of lumber production “It is difficult to stop recording these instances of how the American lumberjack “tied into” their work in France.” He then continued to quantify even more feats in metrics I don’t quite understand but sound big, “The 6th Battalion, working for the British Army at Castets, cut 124,242 feet in nineteen hours with a twenty-thousand Canadian sawmill, and 72,697 feet in twenty hours with a French band mill whose makers would have been aghast at such performances. The 13th Company, at Brinon, cut 1,361 pine logs on a “ten” mill in twenty hours, with a yield 53,895 feet of lumber. Many of the American “twenty” mills cut steadily upwards of 1,200,000 board feet per month, and several of them exceeded 1,200,000 board feet per month, and several of them exceeded 2,000,000 feet monthly on their best runs. The spirit of ‘hitting her hard’ pervaded every camp.”

But Charlie never saw the camps in France.

Charlie enlists

In June, 1917, the blue-eyed, light-haired man of medium build registered for the draft as required in Phillips County, Montana. His occupations were listed as Justice of the Peace, Farmer, and Lumber dealer. However, he did not wait for a call but went to Spokane and entered the Army as a volunteer and trained at Fort George Wright. He was ready to serve his country.

He wrote home to a friend, “How does this war situation seem to take with the people around there and what is the general feeling of the conscription proposition? Most of us around here are ready to go as soon as we feel we are really needed, even, though, most of us are just commencing to make good and see a few dollars roll around. However, America first, last, and always, and in the good old U.S.A. far as, Montana forever!”

US Forestry supports the War

The lumber industry supported the war effort and sent their best, their brightest, and their most able-bodied men to the army. The army was looking for experience, and the industry put up fliers encouraging men to enlist, put advertisements in the journal, and asked managers to encourage good candidates towards the war effort—in many cases sacrificing the company’s own interests to send valued employees oversees.

Charlie was a valued employee and well-liked. A manager of the Rogers-Templeton Lumber company, where Charlie managed a lumber yard, wrote about Charlie that the company “appreciated highly his mighty good qualities.”

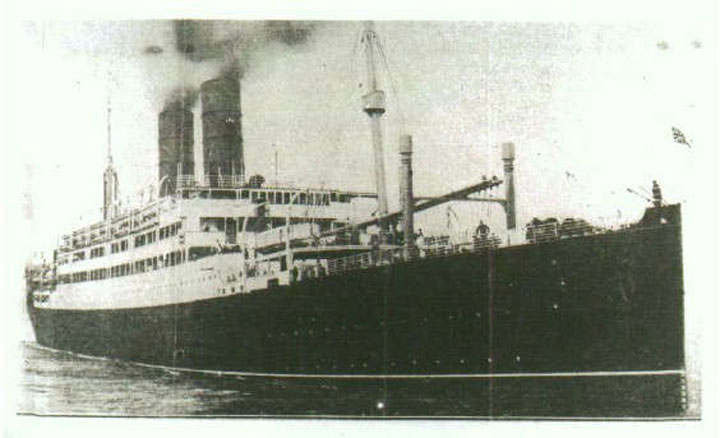

The 6th Battalion, 20th Engineers goes to sea

The Sixth Battalion was ordered organized December 7th, 1917, and reached full war strength when several hundred men, including Charlie, from the Northwest and Great Lakes regions arrived at Camp American University in Washington, D.C., on January 1, 1918. On January 22, the battalion hiked under full pack for 5 ½ miles through snow to Fort Meyer where they caught the train to New York. They boarded the S.S. Tuscania on January 23 and sailed for Halifax to meet a ship convoy headed to Europe. Ultimately, the Sixth Battalion intended to go to Le Havre, France.

February 5th, 1918

On the evening of February 5th, 1918, the convoy rounded the north of Ireland and headed south towards the North Channel between Ireland and Scotland. The rocky Irish coast was visible from starboard and the cliffs of Scotland visible off the port bow before the sun set shortly after 5pm. The soldiers report it was quite dark by 5:30pm. Just before 6pm, the second torpedo from the German U-Boat U-77 struck the Tuscania between the engine room and the stoke hole on the starboard side. The resulting explosion sent a spout of water, steam, and debris upward and destroying lifeboats hanging in their davits beyond use. The Tuscania listed starboard and began to settle aft. She was going down.

A soldier’s account says, “Before the crash had died away every man was on his way to his post. The corridors, passage ways and stairways were a seething mass of olive drab streaming for the decks. The rush was devoid of all hysterical excitement. Each man was excitedly cautioning his neighbor to ‘take it easy,’ ‘don’t rush,’ ‘don’t crowd; she isn’t sinking’; yet he was using his elbows, feet and hands in regular mess-line tactics to further a speedy arrival at his lifeboat.”

Charlie assembled with his company on the dark, slippery decks but went back to grab some important company papers. He became separated from his squad but it is presumed he managed to get onto one of the lifeboats before they were all launched by 7pm. It must have been a harrowing experience. The soldier goes on to describe the launching of the lifeboats:

“With all indications of a speedy sinking staring us in the face, we worked feverishly to lower the lifeboats and cut away the rafts. Pitch darkness made our work more difficult. Here and there a pocket flashlight came into play. Later the auxiliary lights were turned on and we could better see what there was to do. The work of lowering the lifeboats proved discouraging. Not only had we lost several, due to the terrific effects of the explosion, which had thrown a sheet of flame and debris two hundred feet into the air, but we discovered boat tackle in many cases to be fouled or rotted and unfit for use. Some of the first boats we attempted to lower were capsized in midair, spilling their occupants into the icy water. The high seas running and the darkness made the rescue of these men almost impossible. Occasionally we got a boat away good with nothing more serious than sprung planks or missing rain plugs. These difficulties were overcome by bailing with service hats which served the purpose very well. On the port side the launchings were accompanied with another handicap. The Tuscania had acquired such a list that we found it necessary to lower lifeboats down the rivet-studded sloping side of the ship with the aid of oars as levers. In all some thirty lifeboats were launched, and perhaps twelve of these were successful.”

There were still many troops on board after the lifeboats departed but destroyers from the convoy, the Grasshopper, the Mosquito, and the Pigeon, sidled up to the sinking Tuscania and rescued those still aboard. A soldier describes this rescue, probably by the H.M.S. Pigeon, as follows:

“Suddenly on the starboard, out of the darkness, a tiny destroyer came sidling up to the troopship. With a display of seamanship nothing short of marvelous she approached near enough for the men to be transferred to her deck. Some times almost hidden by the roll of the big ship, the destroyer clung to us. Ropes were let over the side and several hundred of the boys went over. When the destroyer was loaded to the limit she steamed away, leaving a few boys dangling to the sixty foot ropes. It was here that one of our cooks, a two – hundred pound specimen, surprised us all and no less himself, by climbing all the way up to the deck again. When asked to demonstrate his feat a few days later in our Irish camp, he was unable to climb the height of the rafters in our barracks.”

The soldier’s fate

The soldiers rescued by the destroyer typically fared better than those in lifeboats and were safely landed in Northern Ireland within a few hours.

Residents from both sides of the channel, Ireland and Scotland, rushed to the aid of the lifeboats and anyone in the channel or reaching their shores. There are many reports of heroism of people braving the water in trawlers and fishing boats, despite the U-Boat threat, to rescue the victims. There are other reports of retirees scaling the steep, sharp cliffs of Scotland to try to rescue those who were being crashed upon the rocks by the current. Some of these reports are even more amazing when one remembers that all the able-bodied young men from these communities were already away fighting the war. The heroes were the everyday folk not at the front.

The shores of Islay were particularly bleak. The wind and current pulled the small lifeboats and rafts toward the island’s more southerly point, called the Mull of Oa. Here, there is no place to beach. The rocky shoal ends in steep cliffs, some as high as 600 feet. As the waves push the boat to shore, the rocks break up the small boats leaving their occupants to fend for themselves, mostly unsuccessfully, among the rocks.

Reports of the dead

Reports of the Tuscania reached the US newspapers on February 7th. The country rejoiced when it learned that the initial reports of more than 1,000 men dead were wrong. Only 210 soldiers plus 45 crew of the 2,397 men aboard the Tuscania perished. Nevertheless, this loss of more than 200 men was the largest loss of American life at once to-date in the Great War. It shocked and galvanized the country. Public opinion was outraged at its loss. In response to the disaster, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker stated, “we must and will win the war.”

Many of the dead were from lifeboats dashed upon the rocks on the Island of Islay on the Scotch coast. It was here that Charlie’s body was found washed ashore. The important company papers were still on his person.

Of Charlie, his captain, C. E. Hetrick of Company F, 6th battalion, 20th engineers, wrote to Charlie’s family, “It is with an aching heart that I write you these few lines concerning the death of your son, Charles. He was constantly with me in my company office and I had become as fond of him as if he were my own son, and I learned to trust in him implicitly…Some of his other comrades will probably write you also, as he had made some very good friends among the very best men in his company and all of his comrades feel his loss very keenly. As his captain, I cannot say too much for him.”

Laid to rest

With the war on, it wasn’t possible to ship the bodies home. Many soldiers, including Charlie, were welcomed to the Island of Islay and buried with full military honors. In 1919, a memorial monument was erected on the island, and the memorial still stands at the edge of the cliffs overlooking the Channel.

After the war, the bodies were exhumed and all but one were repatriated to the United States or buried at the American Cemetery at Brookwood in Surrey, England. Private Roy Muncaster’s family asked that he not be disturbed and the residents of Islay promised to look after his grave as if he were one of their own.

Charlie’s body was laid to rest in Pine Wood Cemetery, Wausau, Wisconsin, on October 18, 1920. He was laid next to his grandparents, Johanna Swanson (1834-1917) and Samuel Swanson (1834-1920), whom he had known well.

*Descriptions of lumber country may or may not be exaggerated as is traditional. Paul Bunyan is an oft-sited folk hero of the lumberjacks with his own storied history. Michael Edmonds, in his 2017 book “Out of the Northwood: The Many Lives of Paul Bunyan” notes that the earliest verbal accounts of Paul originated about 10 miles away from where Charlie was born and about 5 years earlier. I like to imagine young Charlie hearing campfire stories of Paul Bunyan and growing up with some of those legends.

Special thank you to Gloria Rahalf of the Northwoods Genealogical Society for her help in finding details about Charlie’s family and life in Wisconsin.

You can read more accounts here of

The Great Northwoods:

The Camp 5 Museum and Steam Train (http://www.camp5museum.org/) (Open summer only)

Paul Bunyan Logging Camp Museum (http://www.paulbunyancamp.org/history_of_logging.phtml)

The 1895 History of Upper Wisconsin Counties (http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm/ref/collection/wch/id/6854)

The Sixth Battalion, 20th Engineers:

The Sixth Battalion of the 20th Engineers (http://www.20thengineers.com/ww1-bn06.html)

The Forestry Engineers (https://foresthistory.org/digital-collections/world-war-10th-20th-forestry-engineers/)

The S.S. Tuscania sinking:

Islay and the Loss of the Tuscania (http://www.islayinfo.com/loss-troopship-tuscania-islay.html)